The winter of 2017-2018 has been one to remember. Freezing temperatures all the way to the coast has “burned” mangroves, perhaps for the first time since the big freeze of 1989. Ice-covered highways and bursting pipes shutting down most of south Louisiana for several days. The Saints losing in a nail-biting playoff battle against the cold-thriving Vikings (ouch).

So how does the icy weather jive with the first and second reports EVER of Limpkins in Louisiana!? The Limpkin is a tropical species typically found in central Florida south through the Caribbean, Central America, and northern South America. Whatever the reason, it’s an exciting moment in Louisiana birding.

The first-ever Louisiana Limpkin report came from Lake Boeuf near Thibodaux, during the Audubon Christmas Bird Count on 30 December 2017. Josh Sylvest found and photographed four birds, representing the first state record. As exciting as this was, the birds were located in a corner of the lake that was barely accessible because of extreme shallow waters.

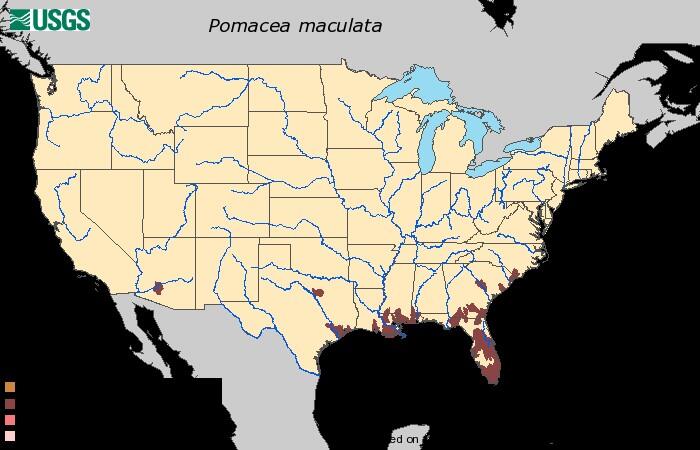

One month later, Michael Autin, a Terrebonne Bird Club member, located two more Limpkins about 100 feet off a busy road in Houma! These birds have since been chased and now seen by just about every birder in Louisiana (ahem, Katie Percy), and have put on quite the show. Ogling birders have seen them eating invasive apple snails (Pomacea maculata) and clams, calling to each other, and passing snails to each other. A few lucky observers also witnessed copulation, and now evidence of nest building! Are baby Limpkins in our future?

With multiple “groups” of Limpkins in Louisiana, including an apparently mated pair, it seems unlikely that they just suddenly showed up in the middle of an icy winter. The freshwater marshes of Terrebonne and Lafourche Parishes are extensive and relatively under-birded. Heck, these birds could have been around for months (or longer?) going undetected by the keen eyes of birders. They superficially don’t look all that much different from an odd ibis, and might be easily overlooked by a non-birder. But despite the superficial similarity to other long-legged wading birds, Limpkins aren’t closely related to anything else on the planet, and instead thought to be a distant cousin of the cranes (Gruidae) and rails (Rallidae) in the Order Gruiformes.

Limpkins are a bizarre beast in other respects, too. For one, they molt backwards, meaning the flight feathers are replaced in a sequence opposite of most other birds. The molt begins at the outer primary and progresses inward, whereas in other birds the molt begins at the inner primary and progresses outward. I’m only aware of one other species on the planet that molts in this sequence: the Lesser Jacana of Africa. Although unrelated to each other, both the Lesser Jacana and the Limpkin are closely related to species that drop all of their flight feathers at once during the annual molt (called simultaneous molt). As such, if Lesser Jacanas and Limpkins diverged from simultaneously molting ancestors, the “sequential molt” genes would have been “turned back on,” and a reversal in the physiological cues that determine the sequence of flight feather replacement may have led to this unusual molt strategy. It’s just a hypothesis, but an interesting case study.

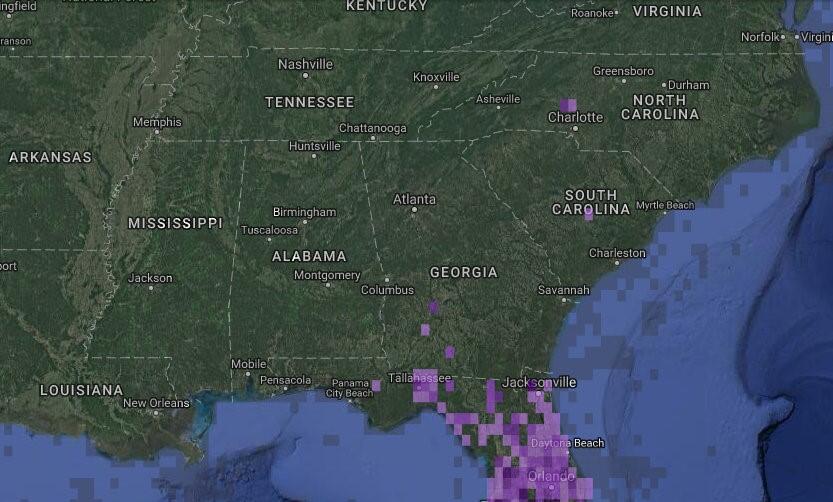

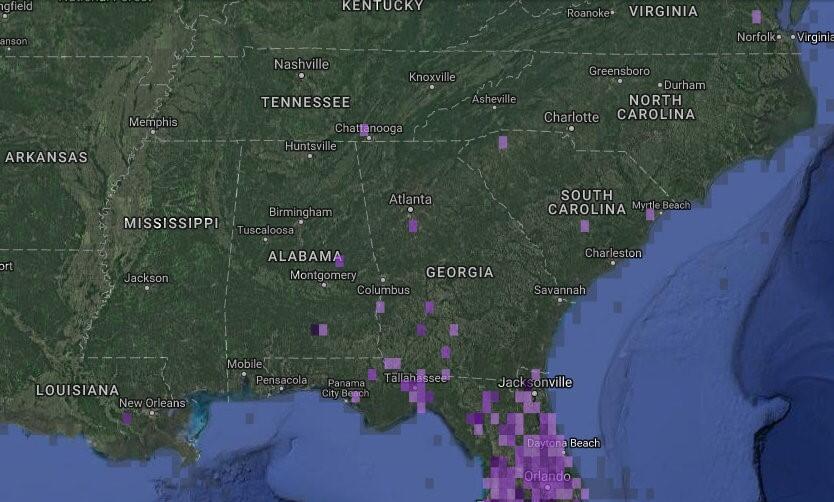

So how did the Limpkins get to Louisiana, nearly 400 miles west of the western-most resident population in Florida? And when? This is a non-migratory species, and usually not prone to vagrancy, but 2017 was different. There was an irregularly high number of extralimital records in 2017, and these vagrants ventured farther west than normal, culminating in two Louisiana records. What is interesting is that all of these records (except the two Louisiana ones) were discovered in summer, with couple lingering into fall, suggesting a period of dispersal from Florida that began and perhaps ended many months ago.

Could it be possible that Limpkins have been in remote southeastern Louisiana wetlands since this past summer, and have only just become “discovered”? It wouldn’t be the first time birders were a little behind the 8-ball – the famed Ringed Kingfisher of Lake Martin was known by a couple of photographers for three and a half months before a birder “discovered” the bird, alerting the broader birding community about its presence.

Avian range expansions often progress with short jumps, like the spread of Inca Dove from western to eastern and northern Louisiana over the 1990s and 2000s. But birds can make long jumps, too, like island colonization events (queue Darwin’s finches here). The ridiculous abundance of invasive apple snails in southeastern Louisiana may just be facilitating such a long jump. But it seems equally plausible that other Limpkins have gone undetected in remote and apple-snail-infested wetlands of southern Mississippi and Alabama.

We at Audubon Louisiana would also like to express our gratitude to the proactive efforts of Kathy Rhodes of Terrebonne Bird Club who engaged her local Terrebonne Parish leaders to provide protective fencing that will keep viewers at a safer distance for the birds. The Parish is also considering an ordinance to declare the area a temporary Conservation Area!

It will be exciting to see how this plays out. Birders between the Florida panhandle and southeastern Louisiana should become familiar with the loud calls of Limpkins, and should be listening and looking for them in emergent freshwater wetlands, particularly where invasive apple snails are taking over. May we all have baby Limpkins in our future!